Breeders, Bankers and Bankrupts

(continued)

2. Bankers and Bankrupts

During the late eighteenth century many landowners moved into banking. The bank of Surtees and Burdon at Newcastle, known as the 'Exchange Bank' was opened early in 1768, the original founders being Aubone Surtees - the father of Bessie Surtees and father-in-law of John Scott 1st Lord Eldon - and Rowland Burdon of Castle Eden, MP for Sunderland; and in 1788 a branch was established at Berwick. John Bailey and Christopher Mason were involved with the Berwick Bank. Christopher Mason was also in partnership with Arthur Mowbray in the Durham and Darlington bank.

John Brandling joined the Exchange Bank upon the death of Aubone Surtees in 1800, which bank, however, failed in 1803.16 The liabilities against the estates of the partners were:

| Aubone Surtees | £75,288 | 5s | 7d |

| John Surtees | £73,841 | 13s | 4d |

| Rowland Burdon | £85,368 | 8s | 10d |

| John Brandling | £127 | 0s | 3d |

| John Embleton 17 | - | - | - |

Brigadier-General H. Conyers-Surtees in his Records of the Family of Surtees relates that these debts were paid in full, and reports the failure was caused by the rash speculations of the younger members of the firm.

John Mason, father of Christopher Mason died in 1813. At this juncture Christopher Mason withdrew from the Durham and Darlington Banks. His partner in the bank Arthur Mowbray was declared bankrupt in 1815 when Mowbray & Co. collapsed in the post Napoleonic War depression, along with a number of other north-eastern banks. Arthur Mowbray had been the receiver and manager for Sir Henry Vane Tempest's estates and Receiver-General of Rents and Fines for the Bishop of Durham, two of the most powerful appointments during the development of the collieries in County Durham in 1795.

Like a phoenix rising from the ashes of the Durham and Darlington Banks, Mowbray became involved with the Hetton Coal Company from 1820 until 1832, and had cleared his debts by 1823. The shares he bought in 1820 at £250 had appreciated to £18,000 each when he sold them in 1832 to fund his retirement. He died at Hurworth in 1840 when most of his property and shares were left to his widowed daughter Hannah Jane Cochrane.18

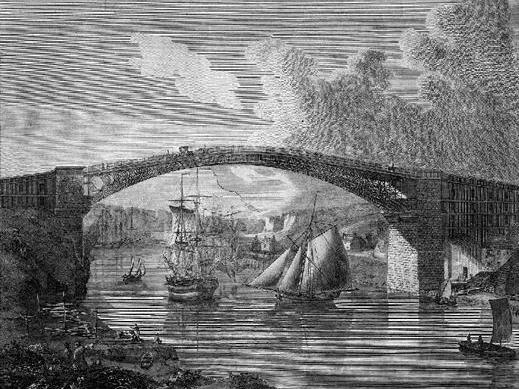

Despite Mowbray's resilience, Christopher Mason's withdrawal from the banks in 1813 may not have been without just cause given the experience of another victim of the banking crisis, Rowland Burdon. Burdon had been instrumental in funding and obtaining Acts of Parliament for the iron bridge across the Wear at Sunderland, opened on 9 August 1796.

The single arch bridge of 236 feet 8 inches, with 94 feet clearance at low tide for sailing vessels, had been fabricated at Coalbrookdale from 260 tons of iron, an early example of industrialisation. The total cost had been £34,000 of which Burdon subscribed £30,000. When his bank collapsed, leaving him with liabilities of over £85,000, his shares were disposed of by lottery. The bridge was replaced in 1859 by the Wearmouth Bridge, supervised by Robert Stephenson at a cost of £40,000. Rowland Burdon died at the age of 82 on 17th Sep 1838.19

of Durham. Built by Rowland Burdon Esq. M.P (c.1796). Ref: DUL Topo/ENDU/Sun/A/1.

Christopher Mason's own financial troubles originated in the railway and colliery expansion in the late 1820s and early 1830s. His neighbours at Little Chilton, Edward Wilkinson and John Evelyn Dennison, MP for Ossington in Nottinghamshire, were exploring for coal on their estate, as a colliery already existed at Ferryhill. The Clarence Railway had opened as an alternative route, (from Simpastures to Stockton) to the Stockton and Darlington Railway. The Clarence had also extended to Coxhoe and Ferryhill to service the mining interests of William Hedley (1779-1843). Christopher Mason opened a colliery at Chilton Buildings with an additional lease from the Dean and Chapter to work Leasingthorne [Leasingthorne Colliery, 1836-1967].

The finances of the early railways were never the most solid investments, so that when Christopher Mason died in 1836 the Clarence Railway was dependant upon exchequer loans, partly guaranteed by himself. At the time an Act of Parliament for the Chilton extension to Leasingthorne had not been promulgated.

Dr Winifred Stokes states in her biography of Christopher Mason,

This assertion is born out by later statistics. In 1950 Chilton Colliery had an average weekly output of 7,500 tonnes.21

Conclusion

The Clarence railway route survived the financial traumas of its early days and the section from Ferryhill to Stockton continues to be used daily by freight traffic. Original road bridges which cross the route at Mordon still exist, providing a lasting testament to the foresight of the early investors in new technology of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

The changes in farming practice in the last sixty years have seen the demise of the Dairy Shorthorn and Ayreshire cattle herds, but the Border Leicester sheep continue to provide meat for the population of Britain. The men and women who farmed in Durham and Northumberland during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries have left the nation a tangible and tasty legacy.

This article was written by Tim Brown, with contributions from R. Sewell and the late S. Todd of Ferryhill History Society, and published as part the North East Inheritance Project (2008).

Notes

| 16 | Will of Aubone Surtees of Newcastle, DPRI/1/1800/S25/1-5. |

| 17 | Brigadier-General Herbert Conyers Surtees Records of the Family of Surtees, 1925, p69. |

| 18 | Will of Arthur Mowbray of Hurworth House, DPRI/1/1840/M18/1-3. |

| 19 | Will and four codicils of Rowland Burdon of Castle Eden, DPRI/1/1838/B41/1-5. |

| 20 | Durham Biographies, volume 3, edited by G.R. Batho, p129. |

| 21 | Sedgefield Rural District, The Official Guide 1955, p57. |

| 22 | Durham Biographies, volume 3, edited by G.R. Batho, p129. The finances of the Clarence Railway are explored by Dr Winifred Stokes in a paper 'Who ran the early railways? The case of the Clarence', Papers from the 2nd International Early Railways Conference, 2003. |