The wreck of the Palermo

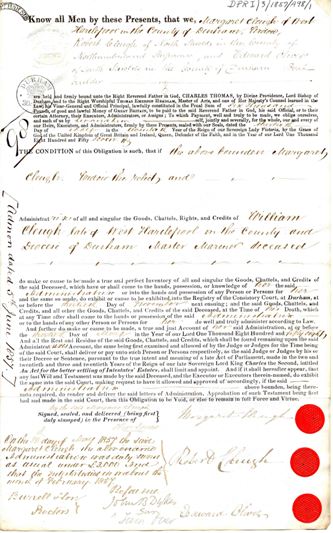

Having made this sworn statement in the bishop's consistory court at Durham, perhaps supporting her statement by showing to the court documentation from the Registrar General of Seamen, Margaret Cleugh entered into a bond binding her to properly administer her husband's estate. It may be that the names and signatures of her sureties were made on the bond on a different day, either beforehand or afterwards. The bond is endorsed with a note by John Lamb a notary public at South Shields in County Durham certifying that Edward Oliver and Robert Cleugh signed and sealed the bond there: they were no doubt busy men, and by doing so it meant that only Margaret Cleugh herself needed to attend the court at Durham that day. Nevertheless, these same men were on 4 June 1857 obliged to attend court and submit a joint affidavit stating that they were financially capable of covering any liability should Margaret Cleugh maladminister the estate. This liability was expressed in the bond as the penal sum, the sum of the penalty should the conditions of the bond be broken. Penal sums on Durham diocese will bonds and on administration bonds such as this one were usually twice the value of the estate in this period. A Schedule or declaration instead of an inventory was also submitted to the court by Margaret Cleugh on the same day, indicating the total value of the estate. This schedule includes an insured value of £2,330 for the Palermo.

Thus, two affidavits, a bond and a form of inventory had been entered into the records of the court. The bishop's officials having been satisfied in the information given to them that William Cleugh was indeed lost at sea, and also having determined the value of the estate and the identity of the next of kin to whom administration should most properly be granted, a formal grant of letters of administration could be made to Margaret Cleugh.

This grant was drawn up and entered as an act of court (DPRI/4/28/153-153A) on 4 June 1857 by Margaret Cleugh's proctor John Burrell (of Burrell & Sons) before James Raine a surrogate in the registry of the consistory court of Durham and in the presence of Joseph Davison, notary public and Durham Deputy Register (Registrar). Although this account of the probate process gives the impression of a convoluted series of transactions in open court, in fact as the Cleugh probate was a non-contentious one these actions were largely administrative and would have occurred within the registry of the court rather than in an open session of the consistory court itself.

Formal grant of letters of administration was made the next day, 5 June 1857. These formally empowered Margaret Cleugh to begin to settle her husband's affairs and apportion his estate. In some cases administration could stutter on for years: whether or not this occurred in this case can not be demonstrated from the Durham diocesan probate records, but as the schedule of William Cleugh's goods, chattels and credits - his personal estate - is not a long one, it is likely his estate was soon settled. The administration grant is dated 5 June 1857, and some seven months later on 11 January 1858 the Court of Probate Act (1857) came into force, removing testamentary probate jurisdiction from the much criticised ecclesiastical courts, and creating the centralised civil probate courts that persist today. From 1858 wills might be proved either locally at District Probate Registries or at the Principal Probate Registry in London. The Principal Probate Registry is now called the Principal Registry of the Family Division, and the Probate Service forms a part of the Family Division of the High Court (administered by HM Court Service).

We can add one short final postscript to this history of the wreck of the Palermo, as revealed in Durham probate records. Among the post-1858 records of the civil Durham District Registry is the will of William Cleugh's father, John Cleugh of South Shields, a ship-owner like his son. The registered copy of this will reveals that having learnt on 16 April 1857 of his son's death, John Cleugh acted swiftly and had a (new?) will drawn up by John Lamb, notary public, on 27 April 1857 at South Shields and also witnessed by Edward Oliver senior. This John Lamb was the same notary public that witnessed Edward Oliver and Robert Cleugh's signing of the administration bond at South Shields, and which business was perhaps done on the same day. Robert Cleugh, also a ship-owner, was John Cleugh's brother and lived across the Tyne from him at North Shields. In his will John Cleugh made Margaret Cleugh and her children and his grandchildren William and Jane the sole beneficiaries. John Cleugh died 15 July 1858, and his will was proved at Durham District Probate Registry 28 September 1858, his estate being valued at £1,500.