Death, Dying and Disposal

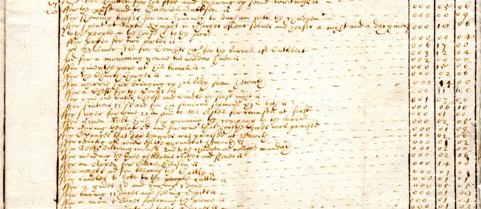

Inventory of Robert Crawforth, curate of Whitworth

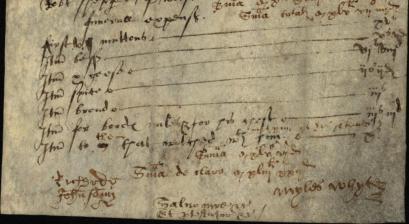

We can go some way to reconstructing the menu of Crawforth's arval dinner or funeral feast in the summer of 1583 as the inventory contains among the list of funeral expenses six muttons, beef, ten geese, spice and bread. It appears to have been a temperate affair - no mention of beer or wine. Also included are the 3s 3d paid for boards and nails for his coffin, and 10s paid 'to them that watched with him in tyme of his sekenes'. On the reverse is an unusually full itemised list of the 9s 8d in fees charged by the probate court, and which include payments to the Spiritual Chancellor of Durham, the Registrar, the Apparitor - an officer who summoned people to court - and, to a clerk of the judge of the court that day, 2d 'for wax'. The officials of the bishop of Durham could earn very substantial sums from their offices and their positions were highly prized.

Ref: DPRI/1/1583/C10/2.

Will of Peter Carter of Shincliffe

Will of Henry Shaftow of Berwick-upon-Tweed

Will of William Grey, first Baron Grey of Warke

These are three examples of religious preambles that use language characteristic of first a Catholic, second a Protestant, and finally a Presbyterian. We can see from the highlighting of the catholic-styled preamble of Peter Carter that it drew the attention and probably the disapproval of one of the bishop's officers in the registry or court.

Ref: DPRI/1/1589/C4/1; DPRI/1/1631/S9/1; DPRI/1/1675/G14/1.

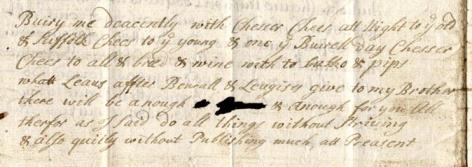

Will of Nicholas Chance of Greenside, yeoman

Chance made his will between June and October 1740, leaving strict instructions for the distribution of cheese, bread, wine, 'to bakko' and pipes to the young and old.

Ref: DPRI/1/1740/C2/1.

Account of Cuthbert Ellyson of Newcastle upon Tyne

The account reveals that Ellyson died at Heworth, and lists the sums paid for the coffin, his widow's mourning gown, the sweetmeats, cakes, cheese and candle, church charges, and the wine given to the gravediggers.

Ref: DPRI/1/1632/E3/4.

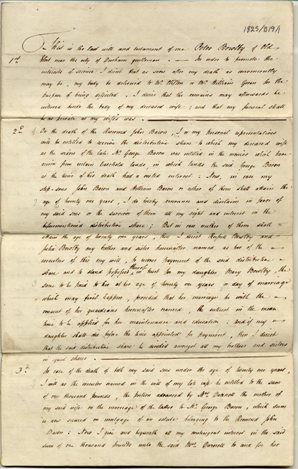

Will of Peter Bowlby of Durham City, gentleman

Bowlby begins his will with a wish to 'promote the interests of science' by ordering his dissection by either Mr Clifton or Mr William Green 'as soon after my death as conveniently may be'. Such a request is unusual, even today: it is estimated medical students in the UK require about 1,000 cadavers for study purposes each year, but generally can obtain only two-thirds of that number. By current law testators must specifically bequeath their bodies to scientific research, and a witness must be present when they do so.

Ref: DPRI/1/1825/B19/1.

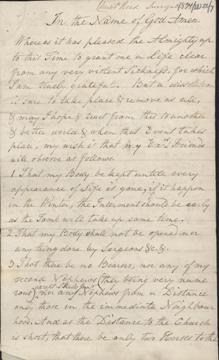

Codicil of Steven Wright of Dockwray Square, Tynemouth

Stephen Wright's second codicil provides elaborate arrangements for his coffin and burial, including an insistence that his body 'shall not be opened nor anything done by Surgeons'. This codicil was written in 1831, six years after the Burke and Hare scandal in Edinburgh and one year before the Anatomy Act was passed. Leaving nothing to chance, he suggests that if he is to have a lead coffin, 'it would be advisable to move my body down stairs, to avoid any accident to the stair case &c.' Such concerns were not uncommon: Hannah Landell a spinster of Newcastle upon Tyne requested in her 1821 will her body should remain in bed undisturbed and the coffin left open 'until a change takes place'.

Ref: DPRI/1/1834/W22/7.

Account of Thomas Bell of Kyloe

Bell's father entered this account of his administration of the estate. The account records that Thomas Bell drowned in an accident, probably just off the coast nearby. The body was recovered, and the coroner called. Raph Reveley's fee for viewing or 'crowning' the body is listed in the discharge - 13s 4d. The persons who searched the water and then carried the body to its burial received 6s 8d.

Ref: DPRI/1/1635/B2/1.

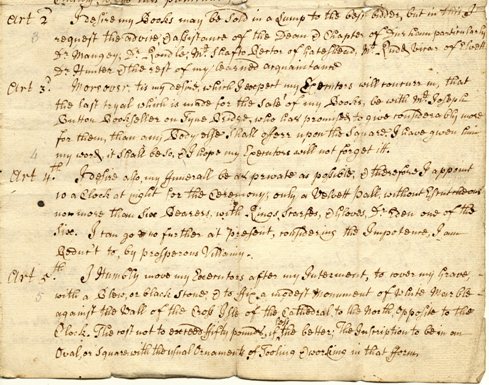

Codicil of William Hartwell, prebendary of Durham Cathedral

An extract from a codicil to the will of William Hartwell, prebendary of Durham Cathedral, who died in 1725. By his will, he left money to a range of charitable causes, including 20 pounds yearly 'to the Jayl of Durham, for the use and benefitt of Insolvent Debtors there' and 6 pounds for a schoolmaster in Stanhope, 'provided he Teach nothing but to read and write in the English Tongue, without any Greek or Latin.' In this extract, he sets out arrangements for the sale of his books, his funeral arrangements, gravestone and memorial tablet in the cathedral.

Ref: DPRI/1/1725/H6/3-4.

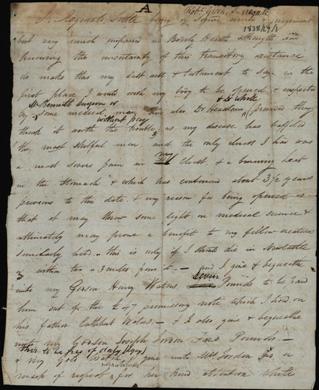

Will of Reginald Little of Newcastle upon Tyne, merchant's clerk

His own health clearly preoccupied Reginald Little, who made his will when 'very much impaired in bodily health and strength' and who requests his body 'to be opened & inspected by Mr Bennett surgeon or some medical man and also Dr Headlam & Dr White (provided they think it worth the trouble without pay) as my disease has baffled the most skilful men, and the only ilness I had was a most severe pain in my chest and a burning heat in the stomach & which has continued about 3½ years previous to this date, & my reason for being opened is that it may throw some light on medical science & ultimately may prove a benefit to my fellow creatures similarly held - this is only if I should die in Newcastle or within two or 3 miles from it'. The later insertion of additional medical men's names creates the impression Little was uncertain the medical men would find his corpse sufficiently interesting and was widening the field: the provisions of the 1832 Anatomy Act had largely met the needs of anatomists.

Ref: DPRI/1/1838/L9/1.

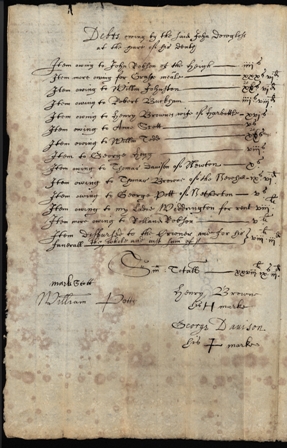

Inventory of John Douglas of Harbottle in Alwinton, servant and shepherd

Douglas was employed by Sir Edward Widdrington of Harbottle, and in his will he makes Lady Widdrington his universal legatrix, noting gratefully that most of what he had he had earned in their service anyway. She appears to have ensured that his funeral passed with proper ceremony, the bill for a 'crooner' appearing in the inventory. Crooner is a northern and Scottish word, and in this context probably means a person who was paid to lead the laments.

Ref: DPRI/1/1642/D5/3.