Health and Medicine

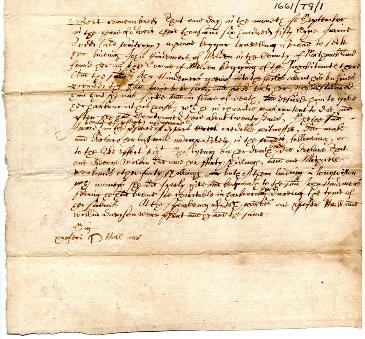

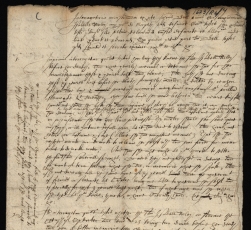

Nuncupative will of Jane Todd alias Wintropp, widow, an itinerant beggar

Jane Todd was 'poore beggar travelling abroad to seeke her liveing' who died at Meldon, Northumberland, in the house of John Hindemers who had taken her in having found her sick in the fields out of town. Hindemers' charity was rewarded when Todd bequeathed him all she owned: 2 debts of 40 shillings. From medieval times charitable 'hospitals' and latterly tax funded almshouses and workhouses operating under the Poor Laws catered generally for the destitute and the infirm with perhaps some incidental and inconsistent provision of medical care. It was not until 1751 that an infirmary dedicated solely to the treatment of the sick was established in Newcastle. From 1777 a dispensary was able to provide professional out-patient care. A dispensary was established at Durham in 1785, and an infirmary in 1793.

Ref: DPRI/1/1661/T9/1.

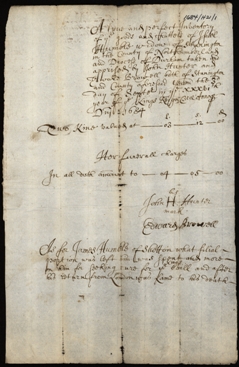

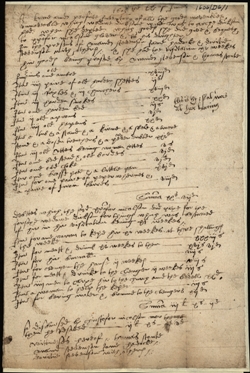

Inventory of Isabel Humble of Stannington

There was long the superstition that King's evil or scrofula could be cured by the ceremonial touch of an anointed king or queen. Introduced to England by Edward the Confessor, the practice of 'touching the king's evil' continued up until 1714. The monarch would touch the sore with a gold coin, which coin was then given to the sufferer as a dole: after 1626 applicants for the touch were required to be certified by their parish. In this case the journey to London by James Humble, perhaps the husband of Isabel, was in vain: 'what portion was left him was spent and more on him for seeking cure for the King's evil and after his return from London was lame to his death'. This tuberculous disease is rare today, and is treated with antibiotics or surgery.

Ref: DPRI/1/1684/H21/1.

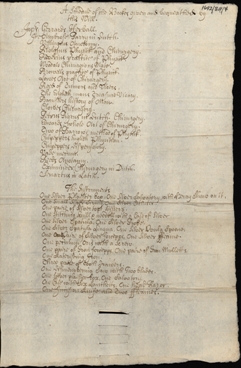

Interrogatories of John Bell, a cousin, to the witnesses of the will of Issabell Rydley of Morpeth, widow

These are questions put to the witnesses to establish or challenge the validity of the will, each interrogatory beginning with a short Latin clause but then continuing in English. Probates of uncontentious wills could be obtained quickly in a 'common form' administrative process often involving surrogates of the bishop's judge (called the 'Official Principal') conveniently located around the diocese; but where a dispute arose then the will required a sterner test of its validity 'in solemn form' and which took place in the consistory court. This process involved the cross-examination of witnesses and the deliberation of the Official Principal, who finally produced 'sentence' (judgment) on the case. Rydley appears to have made on the same day both a written and a nuncupative will. It was alleged that Ridley had for a long time been 'as a childe being not able to governe her self' and so not capable of making a valid will and testament. In this instance a summary of the nuncupative will was drawn up from the statements of the witnesses by the judge. Officials were often pragmatic and would conscientiously seek to correctly interpret a testator's wishes and, unless perhaps confronted by a person proscribed from making a will, would not void a deceased's final will out of hand. Those persons suffering mental illness, and who were without means, could be cared for in workhouses established under the Poor Law, sometimes in specially designated rooms. Newcastle's first dedicated Lunatic Hospital was opened in 1764, and a private Licensed House was established at Bensham, Gateshead in 1799.

Ref: DPRI/1/1623/R6/4.

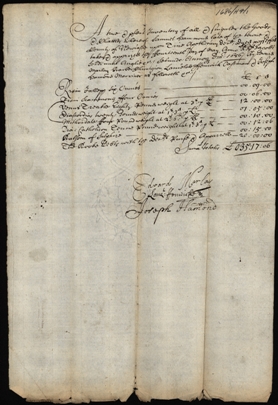

Inventory of Alice Dickson of Newcastle St Andrew, widow

A number of lazar-houses were established across County Durham and Northumberland, perhaps the earliest being the hospitals of St Mary Magdalen in Newcastle and of St Giles at Kepier near Durham in the 12th century. The former was re-established after the dissolution, much of its work then being taken up with the poor rather than strictly with lepers. In 1606 Alice Dickson was one of these 'pore which was mantaned of the maidlenes'. The inventory contains payments both for when she was being treated for jaundice and then later when for 11 weeks she had the plague. An accompanying letter relates a dispute over the ownership of a pot. Leprosy was already declining in England by this time, but it persists today in other parts of the world. While the disease is now treatable using multidrug therapy, millions of former sufferers remain permanently disabled.

Ref: DPRI/1/1606/D6/1-2.

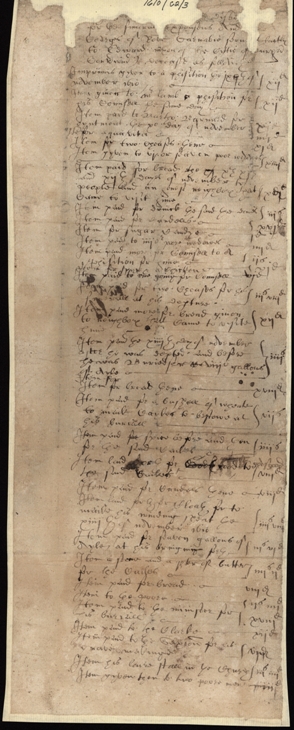

Inventory of Robert Carnaby of Durham St Nicholas, servant

The medical bill for Robert Carnaby is surprising considering his menial status. He was visited by a physician on 9 November 1610 and another physician named Mr Lamb provided a second opinion the same day: each were paid only a shilling for their pains. Probably at their suggestion an apothecary named Bartholomew Barnard supplied an ointment and some aqua-vitae the following day. When considered against Carnaby's personal estate, there are listed a disproportionately high number of expenses relating to his care, funeral and wake, and his employer Edward Nixon, a wealthy Durham cordwainer, is careful to claim £2 2 s against his servant's estate for his other servants watching over him, for spoiled bedding and for the cost of losing these servants' labour during their vigil.

Ref: DPRI/1/1610/C2/3.

Inventory of Samuel Hammond of Newcastle upon Tyne, apothecary

Apothecaries' own inventories are an excellent source for understanding historical medical practice and provide clues to their formularies. Most of the medical compounds listed are no longer in use, having been replaced by safer and more effective alternatives. Resin of jalap and scammony are purgatives; diascord is a herbal medicine; mithridate and Venus (Venice) treacle are generic terms for electuaries, sweet medicinal paste compounds then valued for their properties as antidotes and preservatives; a diacatholicon is a laxative; balsam of sulphur is sulphur dissolved in oil or turpentine.

Ref: DPRI/1/1686/H4/1.

A schedule of books and surgical instruments bequeathed in the will of Henry Shaw of Newcastle upon Tyne, barber surgeon

Working alongside apothecaries were surgeons and physicians, together forming the chief medical professions. In the earlier period there are instances of witchcraft, particularly in the rewarding area of animal practice (both curing and blighting); latterly the probate records of veterinarians begin to occur, and specialisations in medical practice multiply. Such practitioners' probate records can include inventories of their instruments and books, as in this case. Many of the surgical instruments are made of silver as the metal has antibiotic properties. The number of Dutch texts in this inventory may reflect the health of the book trade across the North Sea, but equally Shaw may have trained at Leiden or Utrecht or another of the great medical schools in Holland, then the most advanced in Europe.

Ref: DPRI/1/1692/S9/4.