Wills and Local History

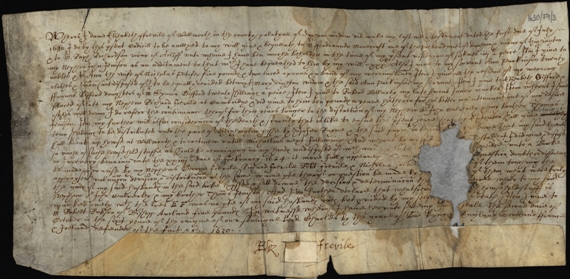

Codicil of Dame Elizabeth Freville of Walworth, widow

In a codicil to her will made in 1630 Dame Elizabeth Freville orders 10s to be distributed to the poor of Heighington every fortnight for up to twelve months 'in consideracion of the dearth & scarcity that is like to ensue this present yeare'. She had already created a charity for the parishes of Sedgefield and Bishop Middleham in her will: every year eighty of the poorest parishioners were to receive 2d each, and three local apprentices were to be bound, though not to weavers or any other poor trades as she is careful to stipulate. The land she directed be purchased to fund this charity, Poor Carrs (86 acres), can be traced in the Bishop Middleham 1839 Tithe Map under the ownership of The Poor of Sedgefield. Freville's charity is now administered as part of a larger fund of Relief in Need Charities for parishes in the area, and regulated by the Charity Commission. In 2007 £23,835 of the fund's £29,391 income was directed towards helping those in hardship, need or distress.

Ref: DPRI/1/1630/F9/3.

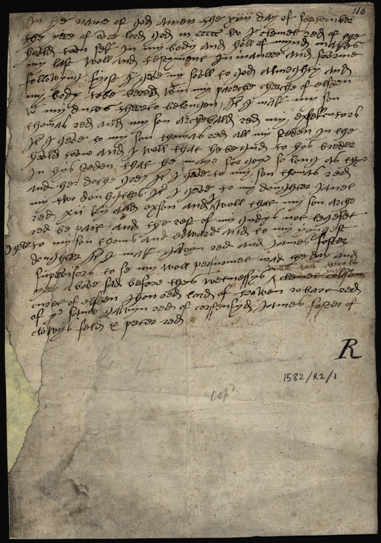

Will of Clemet Red [Clement Reed] of Elsdon

Regional dialects have largely been lost to us, though the odd local word lives on to confuse the foreigner from Durham or Newcastle. As a Reedsdale man Clement Reed spoke a version of Northern English which retained many old Scandinavian words, like bairn for example. He or his local clerk writes phonetically, and thus the speech carries to us through his words: 'I geve to my son Thomas Red all my steden [farm-house and outbuildings] in the hould toune and I woll that he be gud to hys breder [brother] in hys steden that he maye for goye [forego] so long as thye and he dothe gre [agree, 'gree-ah']'. The inventory also includes 'ky [kine]', 'stotys [young castrated oxen]' and 'nout [cattle]'. The language of this will was highlighted by James Raine in the first Surtees Society volume of transcriptions of wills and inventories published in 1835. The different dialects across the diocese - burns in the north and becks in the south for example - reflect its history of invasion and the movement of migrant industrial workers.

Ref: DPRI/1/1582/R2/1.

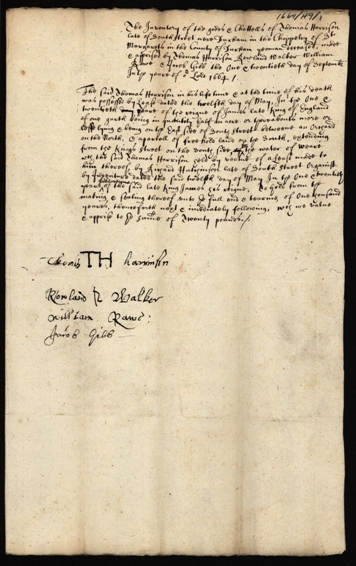

Inventory of Thomas Harrison of South Street, Durham City

Wills were also a means to devise real property, and testators are often careful to delineate the boundaries of a holding, from which a researcher can learn the names of local landmarks, streets and neighbours. In this unusual instance it is a leasehold property's bounds which are so described in Harrison's inventory: half an acre of land 'lying & being on the East side of South Street betweene an Orchard on the North, & aparcell of free hold land on the South, extending from the Kings Street on the South side to the water of Weare'. This 1,000 year lease had been purchased by Harrison in 1623 from Richard Hutchinson of South Street, the organist at Durham Cathedral. Such boundary information can be used with title deeds to map the size and nature of property holdings in an area.

Ref: DPRI/1/1664/H9/1.

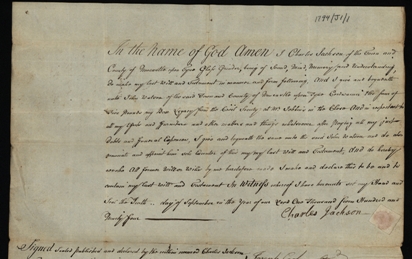

Will of Charles Jackson of Newcastle upon Tyne, glass grinder

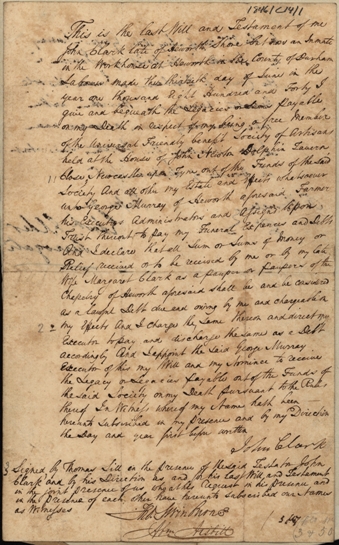

Will of John Clark of Heworth, labourer

Benefit societies became a feature particularly of urban working life from the 17th century, partly replacing the by then moribund trade guilds. Members attended such clubs to socialise, promote and sometimes protect business and even to attend night classes. Like other clubs such as annuity, clothing and burial clubs, benefit societies were also a means of providing financial security to their subscribing members. Payments were made typically to the unemployed or sick, and money loaned and, upon a member's death, legacies paid. Due to their small size and insufficient actuarial expertise many clubs became unsustainable: Newcastle's Keelmen's Society, for example, was forced to close its box and cease payments in 1742. Larger, national and so more secure associations took their place, hence perhaps the 'Universal' in the title of Clark's club. The right to such legacies could be gifted or traded like a bond or share certificate, and where a family was no longer in possession of a man's certificate clubs would publish death notices of members to invite a claim. Benefit clubs were also encouraged by the upper classes and employers, partly as a means of promoting the availability and moral improvement of workers, and also of fostering their financial independence and security.

Ref: DPRI/1/1794/J1/1.

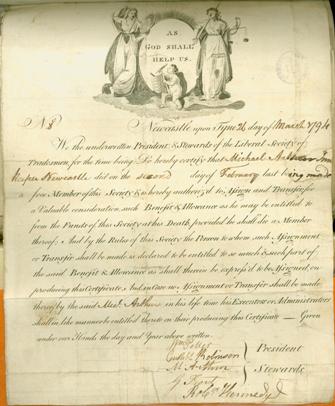

Certificate of Michael Arthur of Newcastle, innkeeper

Ref: Newcastle Libraries, Local Studies and Family History Centre.

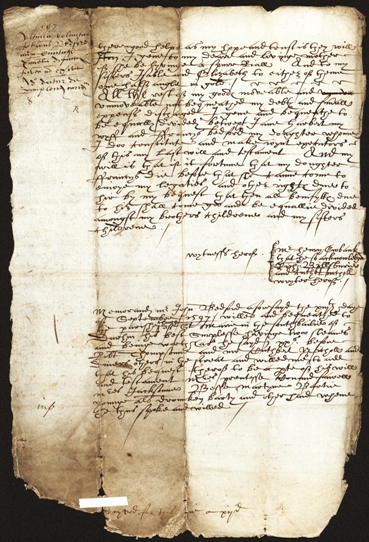

Nuncupative codicil of John Bedford, minor canon of Durham Cathedral

On September 13th 1597, while in the company of Cuthbert Nicholl and Robert Thompsonne in a Durham street, Bedford clearly felt an urgent need to record the gift to his parish church of 'his best surplesse havinge twoo sleaves and beinge worth (as he sayd) xx s [20 shillings]'. Nicholl duly added this bequest to the foot of the will, noting that Bedford's words were also heard by a party of five other persons in the street that day, namely 'Mistress Prentesse, Conand Fawell, Mistress Jacksonne, Besse Martyne and Bartie Younge alias Dronnken Barty'. Unfortunately Mr Younge's will is not found in the probate collection. Many wills are drawn up in rather dry terms and follow standard forms, but colourful local characters do emerge from obscurity on occasion, sometimes in the form of independent minded testators and sometimes, like Dronnken Barty, strolling happily down the high street with some friends on a Tuesday in September.

Ref: DPRI/1/1597/B4/1v.

![]()