Plague

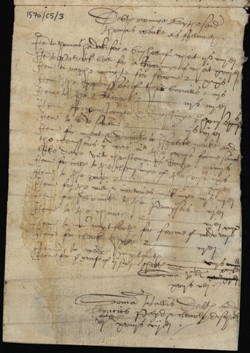

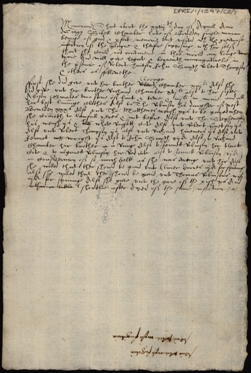

Inventory of Thomas Creake of Newcastle upon Tyne, yeoman

Considering the undoubted dislocation of the time, Creake's appraisers are meticulous in recording the cleansing and the funeral expenses. The cleansers and his wife were in the house from St Luke's day (18 October) to Christmas, nine weeks in total. In this case coal was used for cleansing, a cheaper alternative to frankincense, pitch and resin.

Ref: DPRI/1/1570/C5/2-3.

![]()

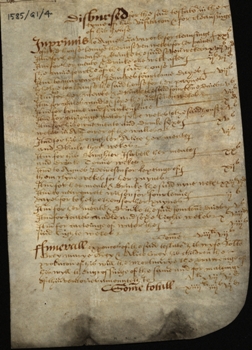

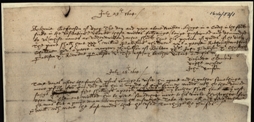

Inventory of William Grey of Newcastle upon Tyne, miller

Grey died of the plague with his wife and four of his five children. The inventory provides unusual detail of their maintenance and care over the ten weeks or so of the 'visitation'. As in this case, when such detailed plague inventories survive it is often possible to reconstruct the regime and economy of their care, and their or the community's methods for trying to contain the sickness. This document reveals that the family appears to have divided, the father spending 6 weeks in a tower in the city walls, perhaps West Spital Tower which stood beside St Mary's Hospital, and his wife and children remaining at home. Four women are named as having stayed in the house to care for the sick, each being paid separate sums for cleansing the house, for their own meat and drink, and for carrying water. Part of the contract between the Greys and their carers appears to have been the provision of meat and drink to the carer for a period even after they left their house and employ. One daughter, Alice, was provisioned for only 3 weeks, while her sister Isabel, who survived, was provisioned for 10 weeks.

Ref: DPRI/1/1585/G1/2-4.

Nuncupative will of Sibell Chamber of Boldon, singlewoman

The virulence of the plague in 1597 might be gauged from the reaction of the unidentified probate court official, who would have been in a unique position to measure the progress of the epidemic, and who scribbled at the foot of the document 'Vive velut rapto fugitiva[que gaudia carpe]' (Live thy life as it were spoil, [and pluck the joys that fly]), one of the classical poet Martial's epigrams (7. 47. 11)).

Ref: DPRI/1/1597/C2/1.

Nuncupative will and codicil of Anthonie Gefferson of Ryhope

Gefferson made his will and codicil 'lynge in a coove in the feild sicke in the visitation'. Clearly he had been quarantined or had quarantined himself in a 'cove' outside Ryhope, and over two days he had made known his wishes to visiting friends. Such extreme measures are not unusual in times of plague and the survival of the word 'spital' in place names today can be an indicator of just such a field as Gefferson died in or of a dedicated quarantine building. The will indicates the testator became confused or was perhaps pressured unduly in his last illness. Two days after making his will Gefferson reportedly denied many of its bequests, and his state of mind at the time is reflected in his last words on the matter, 'Take it you all and give it whome you will'. Perhaps for this reason the probate court did not prove the will.

Ref: DPRI/1/1606/J2/1.

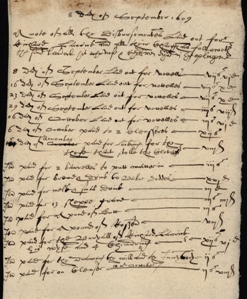

Inventory of Richard Lavrick of Ouseburn

Lavrick died with his wife and four children in the outbreak of the plague in 1609, some time in early October. The inventory is again detailed, and among the disbursements is 8 pence spent on 5 November 'looking for the thefe that stolle the clothes'.

Ref: DPRI/1/1609/L1/4.

Account of the administration of the estate of Jerrard Brown of Newburn, Northumberland

The 'cleansing of the house' is a phrase usually found connected with plague outbreaks, and involved feeding, watering and caring for the sick and then cleansing the goods and the house of the victim. This final part of the process often included fumigating the house by the burning of coal or a pungent mixture of pitch, rosin and frankincense. In this instance the landlord, Mark Errington, accidentally burnt down the house when cleansing it after the death of his tenants Brown and his family. Errington here adds the £10 charge of re-edifying the house against Brown's estate, in the process leaving Brown's sole surviving child Blanch with a balance of only 2s 10d. These events all took place in one of the worst plague epidemics ever recorded in the North of England in 1636/7, and is thought to have reached North Shields from Holland in October 1635. Errington had been appointed by the court as Jerrard Brown's administrator and his daughter Blanch Brown's tutor, and it was not until 10 years later, presumably when she was of age, that Blanch began to contest Errington's administration, forcing him to render this account. She subsequently pursued him in the civil courts.

Ref: DPRI/1/1647/B11/1-2.

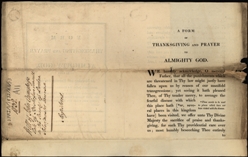

Wrapper of the will of John Armytage of Bishopwearmouth, schoolmaster

Armytage made his will in April 1832 in the aftermath of the Asiatic Cholera Pandemic, then called cholera morbus, which was first noted in England at Sunderland in the autumn of 1831. With the passing of the epidemic parishes were enjoined to offer prayers of thanksgiving, and in July of that year a clerk in the probate registry wrapped Armytage's will in a spare copy of one of these printed prayers. The prayer continues to set disease in an eschatological context. The clerk's use of this document is symbolic of the wider complacency that set in after the epidemic passed, deferring the implementation of the necessary public health measures until the next outbreak in 1849. A young apprentice surgeon apothecary named John Snow who was later to make his name as an anaesthetist and, in the 1849 and 1854 cholera epidemics as an epidemiologist, was treating the miners at Killingworth during this outbreak. The disease today is countered by proper sanitation and vaccination. In 1831 preventative measures existed dating back to legislation in 1710 and 1722, including the checking of ships' bills of health, quarantine and even the destruction of suspect cargo. Threatened by another cholera pandemic in 1871 the River Tyne Port Sanitary Authority established a floating quarantine hospital at Jarrow Slake which continued in commission until 1930. Today Newcastle General Hospital's High Secure Infectious Diseases Unit is one of only two centres in the UK for dangerously contagious viruses.

Ref: DPRI/1/1832/A11/3v.