Inventories in the Probate Records of the Diocese of Durham

by J. Linda Drury

Archaeologia Aeliana, 5th series, 28 (2000); republished courtesy of the

Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Summary

This paper seeks, by describing the collection, to promote the fuller understanding and increased appropriate use of the inventories among the Probate Records for the Diocese of Durham, which included, at the time when most inventories were made (c.1550- c. 1720), Northumberland and parts of Yorkshire and Cumbria as well as County Durham. These are held in the Archives and Special Collections section of the Durham University Library. This material provides important insights into wealth, possessions, social status and legal controls in Northern England over a period of nearly two centuries.

1. The origins of probate inventories

The practice of listing a deceased's possessions goes back to the Roman law of Emperor Justinian

in the sixth century, if not earlier. Roman heirs had the 'benefit of the inventory', by which they

could enter inheritance without liability for debts and claims beyond the value of the estate as it

was established by inventory.1 The relevant English law is set out in three Acts passed

in 1529 which concern the estates of persons dying both testate or intestate; the preambles to these

Acts describe practice as it had been till then.2 The duty was imposed on the executors

of wills, and the administrators of the estates of intestate persons, to make (or cause to be made)

inventories in order to secure the property to those entitled to it; fees were set for the business

according to the value of the estate. In practice, it should be noted, there were many small estates

for which no inventory was ever made.

These inventories are of the moveable goods of deceased persons;3 they are not concerned

with land or buildings owned, although these can be inferred from the lists of crops, stock and contents

- and by reference to the wills and administration documents which can accompany them.

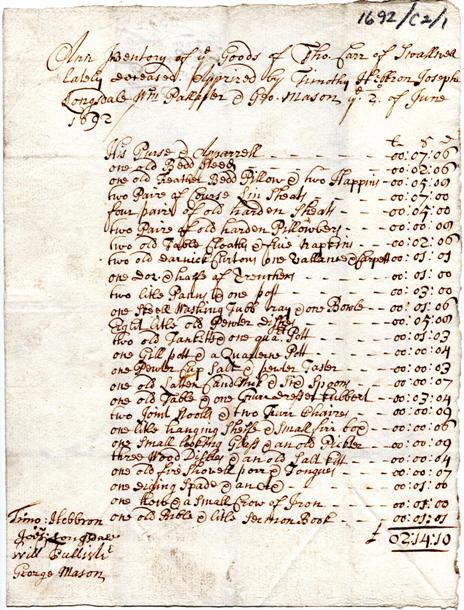

2. The Durham Inventories

For the period c.1542-1600 about 1,000 inventories survive for Durham Diocese, representing a record for

50% of the deceased persons then listed in the Durham Probate records. For the period 1600-1720, measured by

sampling, there are about 12,000 inventories. After 1600, the survival rate of inventories rises. Inventories,

many quite slight, were being made on perhaps more occasions. However, these inventories relate to only a

small section of the total population as a recent study of wills and inventories in Darlington, Co. Durham

for 1600-1625 has shown;4 the parish registers of burials there showed 522 potential testators

yet only 57 inventories survive. At least part of this disparity can be explained by the fact that deceased

persons such as married women and young people under 21 years of age could not usually leave valid wills.

However, the probate bonds survive most unevenly from year to year, making misleading any statistics about

the proportion of inventories among the known names in the probate records. Taking a random year, 1693, as

an example: of the 276 people for whom any will, inventory or bond survives, there are 171 inventories and

70 people who left only a bond. The practice of keeping inventories, except in special circumstances, was

discontinued in the Diocese of Durham around 1720.

The area covered by the Durham Probate inventories is that of the Diocese of Durham before the Dioceses of

Newcastle or Ripon were created: that is County Durham, plus Girsby and Over Dinsdale, (two townships on the

Yorkshire side of the River Tees but still in the parish of Sockburn, County Durham), Northumberland

excluding the peculiars of the Diocese of York (Hexhamshire and Thockrington), including also Alston parish

in Cumberland and the Durham peculiars in Yorkshire (Crayke and Allertonshire). If deceased persons held

property in more than one diocese in the northern or southern Provinces, their wills and inventories should

have been processed in the Prerogative Courts of York or of Canterbury, and are on deposit at the Borthwick

Institute of Historical Research of York University, or at the Family Records Centre in London.

Notes

All the manuscripts and most of the printed material mentioned below are available for

consultation in Archives & Special Collections (ASC) at the Palace Green section of Durham

University Library, Durham City DH1 3RN, tel. 0191 334 2932. The Durham Probate Records,

c.1540-1940, comprise wills, inventories, executors' and administrators' bonds, registers of

wills, probate act books, commissions, monitions and citations, alphabet books and miscellanea.

The various means of reference to these are available at Palace Green. There is other probate

material in other collections at Archives & Special Collections.

When several references are needed within one paragraph, one note number may be used late in

the paragraph to list them all. The years given for Durham Probate Records (DPR) are the

years of reference, which are not always the exact years of the documents.

| 1 | Giles Jacob and J. Morgan, A New Law Dicitonary (1782) unpaginated, see section 'Inventory'. |

| 2 | John Cay, Statutes at Large (1758) vol. I. 765-6 21 Henry 8 cap. 4 The Sale of Lands by Part of the Executors lawful. 766-8 21 Henry 8 cap. 5 What Fees ought to be taken for Probate of Testaments. 768-9 21 Henry 8 cap. 6 Where Mortuaries ought to be paid, for what Persons, and how much, and in what Case none is due. Anne Tarver, Church Court Records Chichester (1995), 56-81, Probate and Testamentary business. The tortuous progress of the jurisdiction of wills and testaments and intestacy from Roman civil law to the bishops of England (who were of course concerned both with souls after death and in receiving bequests to the church) was investigated by the lawyer John Selden in his Tracts (1683) ASC Routh 65.A.5. |

| 3 | In fact 21 Henry 8 cap. 5 said 'a true and perfect Inventory ... as well moveable as not moveable whatsoever'. |

| 4 | J.A. Atkinson, B. Flynn, V. Portass, K. Singlehurst and H.J. Smith, Darlington wills and inventories 1600-1625, Surtees Society 201, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1993. See J.A. Johnston, Probate Inventories of Lincoln Citizens 1661-1714, Lincoln Record Society (1991), xvi-xviii for another discussion on survival of inventories. The Lincoln townsfolk appear to have had a higher material standard of living than those of Durham City. |