Thomas Robson

(continued)

Sanitary Conditions

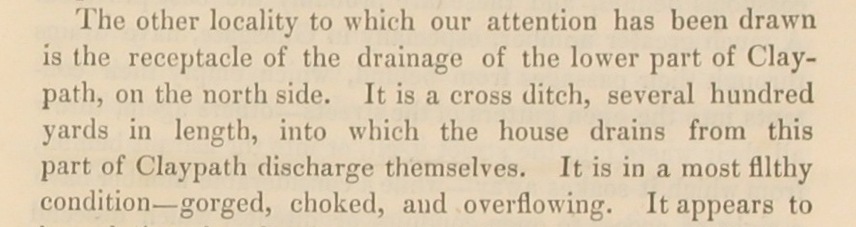

The side-effects of such overcrowding can be traced in the Durham City Health Reports of 1847 and 1849, evidence of a growing national intolerance for the overcrowded, unsanitary and dangerous urban environments that had developed during the rapid industrialisation of the preceding decades, and which conditions were countered with the first of a series of Health Acts in 1848. After the first outbreak of cholera in Sunderland in 1831 Durham, along with the rest of the country, suffered a number of further outbreaks in the following years, and the 1847 report on Gilesgate and Claypath to the Sanitary Association of Durham City reveals why.

Report on the Sanitary Condition of the City of Durham (1847), p.7 [Ref: XL 080 FEN/7].

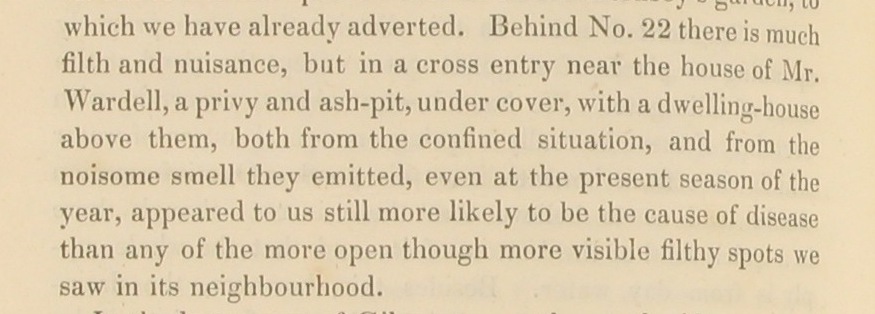

There was no sewer and there were no house drains, privies discharged into the street, the effluent eventually making its way to the River Wear via open gutters, ditches and some covered drains; and house construction and ventilation was also inadequate. Tanners, knackers and slaughterers carried on their trades alongside the streets' inhabitants, and in the houses' yards numerous pigs and other livestock were reared. The very locality of the Robson's home attracted particular comment.

Report on the Sanitary Condition of the City of Durham (1847), p.10 [Ref: XL 080 FEN/7].

Clean drinking water was available from the Pant in Durham marketplace, piped from Ayckley Heads in Sidegate across the river, and there was a trade in clean rain or river water delivered to people's houses for the purposes of laundry and washing - 6 pence a cask to Claypath, and 10 pence a cask further up the hill in Gilesgate. The connection between contaminated water and cholera epidemics was not proved until after Robson's death in 1854. An excellent illustrated article on the health and sanitary conditions in the region during this period is available online as part of the 4Schools learning zone.

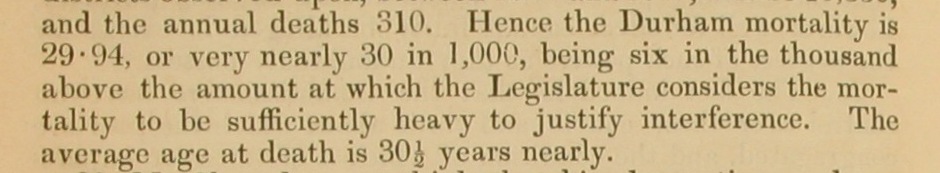

These conditions had a direct impact on people's health, causing life expectancies to fall. The 1849 Report to the Durham General Board of Health found life expectancy in Claypath was 28.7 years, somewhat lower than the city mean of 30.2 years, and higher than that at Leazes Place, just off Claypath on the slope down toward the river, where it was 19.6 years.

Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage, and supply of water, and the sanitary condition of the inhabitants of the borough of Durham (1849), p.8 [Ref: XL 352.4 GEN/1].

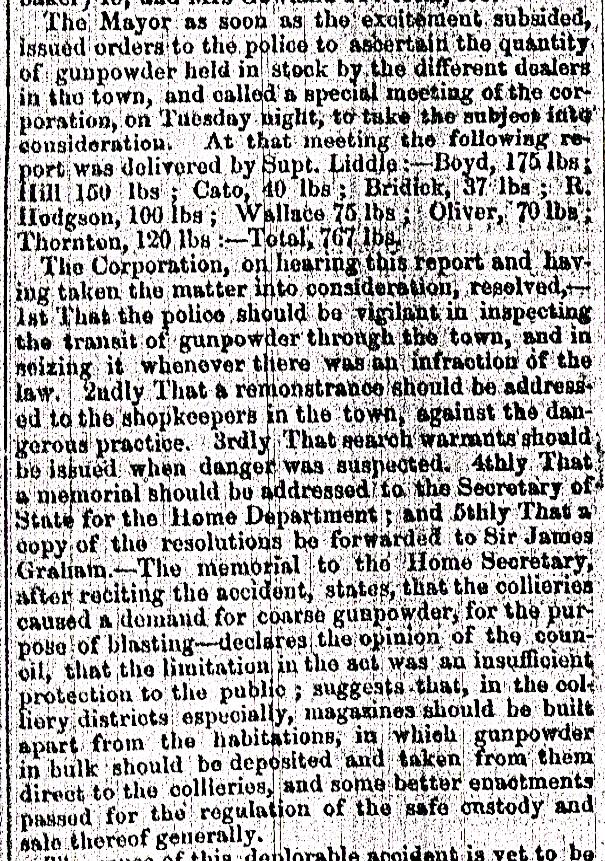

Explosion

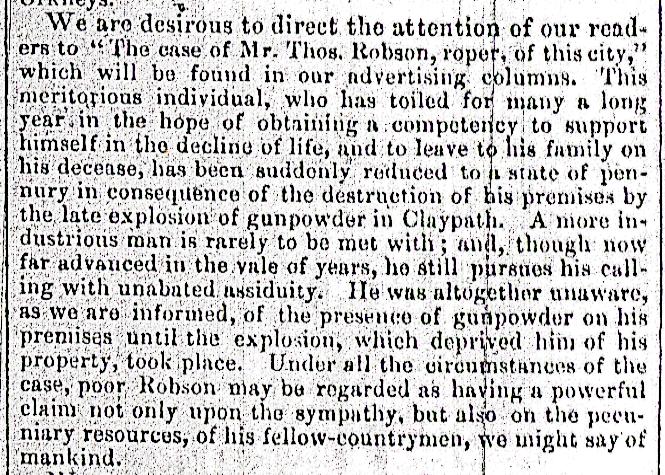

To return to No. 25, this property has also been researched by David Butler publishing in the Durham County Local History Society Bulletin 52 (1994). This is due to an explosive incident that occurred some seven years before Robson's death on 9th June 1845. From the newspaper accounts in the Durham Chronicle and Durham Advertiser we learn that a grocer and tea dealer operated at No. 25, run by a tenant of Robson's named George Steele whose wife and two young children also lived on the property. Like many such shops of the time located in mining areas, quantities of gunpowder were stored on the premises for sale to the public: there was, following the incident, immediate action by the city council to better regulate such storage within the city.

Durham Chronicle, 13 June 1845, p.2.

It was reported that Isabella, Hannah and Jane Robson, dressmakers, and a thirteen-year-old niece were upstairs working

when around 1.45pm Steele's young shop-boy Christopher Spencer placed a lit candle too close to some 11 or 12lbs of black

powder, suffering severe burns in the ensuing explosion which was heard all over the city. The sewing circle upstairs were

blown out into the yard or trapped in the house as it collapsed. All survived the explosion and were rescued by their

shocked neighbours with the help of the fire brigade, although sources suggest Christopher Spencer was taken to the

infirmary in Allergate but later died of his wounds. A shopkeeper across the street, showing a customer a pair of shoes

in front of his store when the blast occurred, was blown back through his shop window into his shop. The damage to

neighbouring properties was later noted in detail in the Durham Chronicle (13 June 1845) - precisely 398 panes of glass

were broken in all.

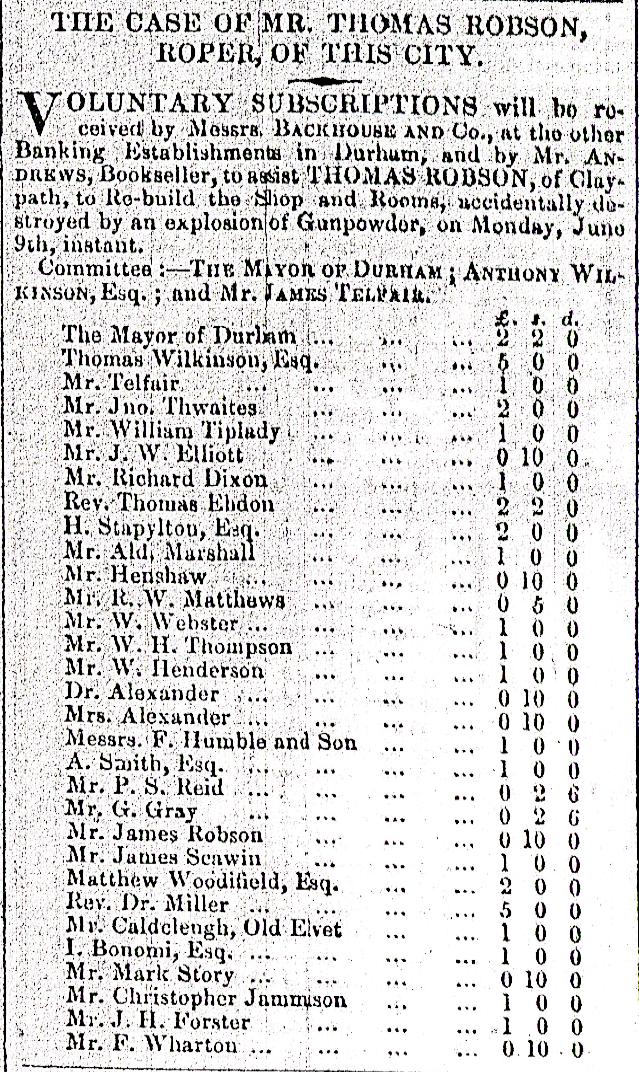

We know the Robsons all survived, indeed the will records that two of the daughters were granted the freehold by their father

in July 1846, just over a year later: this may have been once the property had been rebuilt, helped by a public subscription

for Robson raising £66 15s. This cannot have completely made good the financial consequences of the disaster for Robson, the

cost of rebuilding his house being estimated at the time at around £300-£500. Steele estimated his lost stock to have been

worth between £150 and £200.

The public subscription for Thomas Robson,

Durham Advertiser, 20 June 1845, pp.2-3. |

|

Robson survived to the summer of 1854, the Durham directories listing him at No. 25 Claypath until his death. The 1851 census records he was aged 79 and blind, living with his wife Hannah, and two daughters, who continued to live there and indeed also carried on their father's trade of rope-making until the 1880s. The property of No. 25 Claypath today is occupied by an estate agent, and sits between a derelict cinema and a snooker club.

|

No. 25 Claypath, as it is today. |

This article was written by Pat Atkinson, and published as part the North East Inheritance Project (2008).