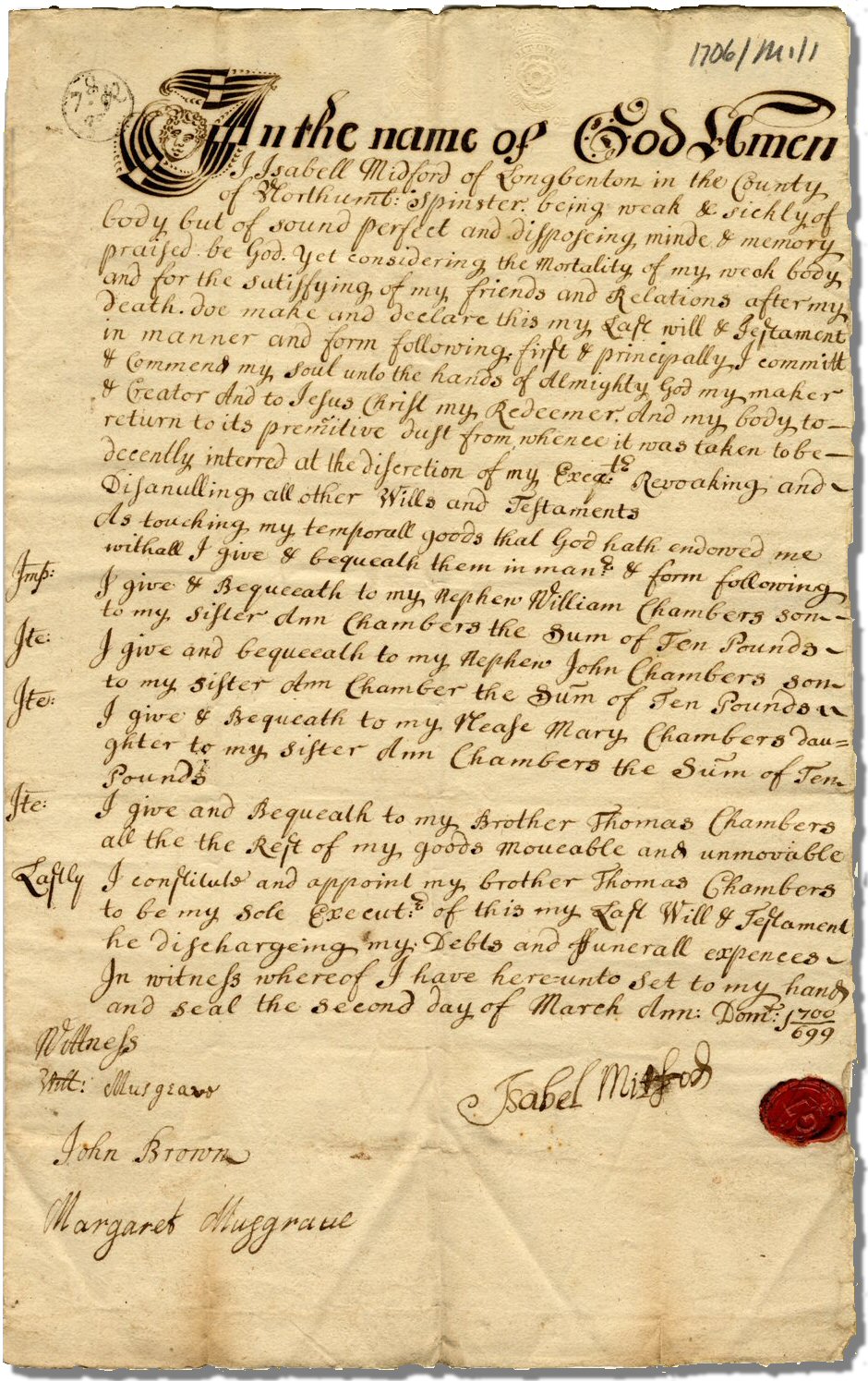

Wills and Testaments

Wills as commonly understood are in fact two different instruments, the will and the testament. In practice, testators usually made their 'last will and testament' in the form of a single document, and a will is understood to mean both. Together they are a means for a testator to dispose of his property after his death.

Who could and couldn't make a will?

A clear qualification for executing a legal instrument such as a will was the testator's sanity, and thus insane or inebriated persons were disqualified, and their wills, if they existed, would be voided. Also voided would be the wills of (unpardoned or unabsolved) convicted felons, attainted traitors, outlaws, suicides and persons under greater excommunication or coercion. Slaves and prisoners were not free to make wills, while married women could make wills, but only with the consent of their husbands, which consent might be rescinded at any time up until probate was granted. While married women might have suffered under this disablement (not removed until 1882), spinsters and widows were perfectly free to act. Children also could make wills, which term was defined in this period as boys aged between 14 and 21, and girls between 12 and 21. The mere possession of goods to pass on was also a clear prerequisite, but the fee structures of the probate courts also sometimes acted as a disincentive to poor persons to use them to obtain probates. Comparable disincentives and incentives existed across many groups and segments of society over this period, and thus while there was a large proportion of society qualified to make and prove a will or to obtain probates or letters of administration, in practice the surviving records contain significant biases in terms of testators' wealth, age and gender.

Why make a will at all?

Wills were and are a formal means of disposing of one's property after death, and perhaps of regulating the care and education of any surviving dependents. As well as providing a means to secure one's descendents' title to one's property, it is also noted by many testators that their will is an explicit means of ensuring that peace prevails after their death and that family disputes might be avoided. Past unpaid dues and disputes might also be finally settled - both among a testator's family and neighbours and also with the church, most often in the form of 'unpaid or forgotten tithes'. Testators frequently also make pious statements and provisions for the health of their soul - the charitable disposition of their temporal goods was after all one of the last good works a person could commission. All in all, a will offers testators the opportunity to make a final reckoning of the goods and property accumulated throughout their life, and to have a last throw at reining in the up-coming generation from those usual excesses as inexcusable to the one as they are inevitable to the next.